If you are a successful small business owner, chances are high that you didn’t get to that place without some setbacks. Rare is the one who never experiences setbacks–in business or life. However, in the sentiment of “turning lemons into lemonade,” it is important that we never allow the setbacks to keep us under. Guy Fieri of Food Network fame certainly has attained some notoriety. We love to watch his show Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives and have visited several of the restaurants featured on the show.

Guy has a certain flair about him–he of the big hair, fancy sports car, and distinctive gotee. Years ago, he and a friend, Steve Gruber, launched their successful food careers with Johnny Garlic’s, two California-style restaurants. The original location in Santa Rosa caught fire one night in 2001. Undeterred, the pair launched another restaurant in 2003, Tex Wasabi’s, which also developed a loyal following. A year later, Russell Ramsay’s Chop House replaced the first Johnny Garlic and the due felt they had come full circle. However, Russell Ramsay’s was slow to get off the ground. Tinkering with the menu and trying to woo former customers back were unsuccessful in helping turn things around.

Guy has a certain flair about him–he of the big hair, fancy sports car, and distinctive gotee. Years ago, he and a friend, Steve Gruber, launched their successful food careers with Johnny Garlic’s, two California-style restaurants. The original location in Santa Rosa caught fire one night in 2001. Undeterred, the pair launched another restaurant in 2003, Tex Wasabi’s, which also developed a loyal following. A year later, Russell Ramsay’s Chop House replaced the first Johnny Garlic and the due felt they had come full circle. However, Russell Ramsay’s was slow to get off the ground. Tinkering with the menu and trying to woo former customers back were unsuccessful in helping turn things around.

Gwen Moran, writing for Entrepreneur, shares Guy’s journey:

…one day, Fieri was sitting at a traffic light, when a guy in the car next to him called over and asked, “Hey, why didn’t you reopen Johnny Garlic’s?” Fieri replied, “I did. It’s the Chop House.” His former customer said he couldn’t afford to eat at the Chop House, and he missed the original restaurant.

That was Fieri’s light-bulb moment. Customers wanted the familiar place they had grown to love. The Chop House gave off a too-rich-for-our-blood vibe—not a good fit for the eatery’s largely blue-collar following. Within a year, the Chop House closed and reopened Johnny Garlic’s, business was up 25 percent within the first month.

Moran says that Fieri learned four lessons from his experience:

1. Listen to feedback from your customers. If Fieri hadn’t paid attention to the guy who spoke to him at the red light, he might have continued trying to get customers to accept something they just didn’t want.

2. Understand your customers’ perception of your business. The Chop House menu wasn’t significantly more expensive than Johnny Garlic’s, but people thought it was. That’s what mattered — and what kept them away.

3. Check your ego at the door. Fieri could easily have let his track record as a successful restaurateur go to his head instead of admitting that the Chop House wasn’t the best fit. Really listen when you get feedback from customers and employees, he says. They’re telling you how you can be better.

4. Don’t give up on your dream. Find a way to make your dream work, even if you have to keep experimenting with new ideas and approaches until something sticks. “Surround yourself with good people who are dedicated and have good ideas, and can help you see what you’re missing. Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water [when times get tough],” he says.

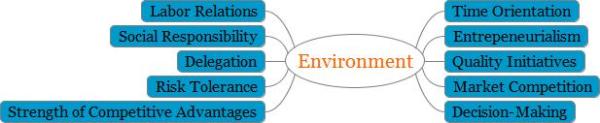

These are four watchwords for any business owner. After we’ve been in business a while, it is so easy to forget what/who helped bring you to that point. Without competitive advantage, a business is not successful. Without customers, there can be no competitive advantage. Inattention to input and thoughts about your business leads to a lack of customers. A willingness to adapt to what the market needs is key to business success. Finally, as Fieri suggests, perseverance is the “glue” that holds it all together.